Seaford’s medieval market square

Do you know where Seaford’s medieval market cross one stood?

Would it help if I said it used to be near Hangman’s Way?

No!

Well how about if I said it is close to where the sarsen stone stands (surely you know Seaford has a sarsen stone), does that help?

If you still haven’t worked out where Seaford’s medieval market cross once stood then luckily you can discover the mystery by reading the fascinating article below kindly submitted by Rodney Castleden, Seaford’s well-known local historian who has published many books on the wonders of Seaford.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could make the market square a special area and add it to the ‘seagulls trail’ allowing tourists and residents alike to learn about our medieval past.

Rodney’s artlcle on the Market Square:-

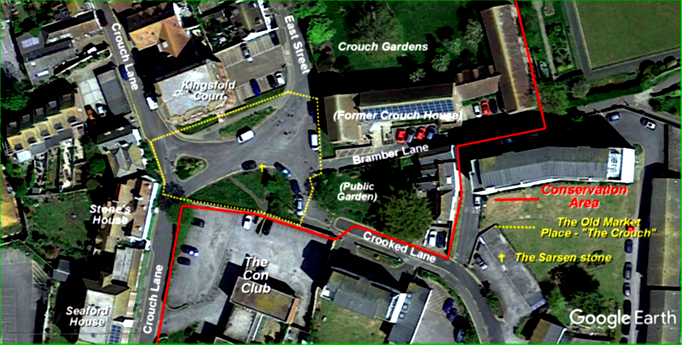

The Crouch

Seaford’s medieval market square is likely to have been the quiet spot, literally a quadrilateral, where five lanes meet. Today it consists of a nondescript spread of tarmac that allows road traffic to pass from East Street across to Crouch Lane. It also includes two patches of grass, the larger of the two a semi-circular patch immediately north of the Con Club site. Two metalled paths cross this grass, leading to a gap in the wall which forms a pedestrian access to the Con Club. In the past this grassy area has been bounded by a low chain suspended between white painted posts, all but one of which have disappeared. A pre-war photo suggests that the grass may have had an iron railing round it. In 2018 the Seaford Tree Wardens planted two trees against the south flint wall to mark the centenary of the 1914-18 war. Both have survived, but show signs of salt damage by winds blowing in from the sea, which is visible from this raised site. In the larger patch of grass, near the centre of the space, lies a flat stone slab, a sarsen stone, of which more later.

Place name evidence

The area in question and the plots and properties adjacent to it have long been known as The Crouch. Crouch House stood to the west. The gardens to the northeast are known as Crouch Gardens. In the mid-nineteenth century, William Tyler Smith built Crouchfield House to the south, on a meadow called Crouch Field, the site of the Constitutional Club, which bought and demolished the house in 1965.2 The fact that high-status houses were built right next to the square suggests that the square held central importance in the town.

Running along the western side of the square is Crouch Lane. The Middle English (medieval) word ‘crouch’ has a very specific meaning that comes from the Latin word ‘crux’, meaning ‘cross’.3 This refers to the market cross which once stood here and which identifies Crouch Square as the location of Seaford’s medieval market. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the Seaford historian Mark Antony Lower mentioned the local tradition, still very much alive in the middle of the nineteenth century, that a market cross once stood on the Crouch.4 It isn’t there any longer, or this article would not be necessary..

The history of Seaford’s market.

The port of Seaford was created in the late eleventh century, immediately after the Norman Conquest, by William de Warenne as an outport for Lewes. The Norman lord of Lewes specifically wanted to control the mouth of the River Ouse to oversee the many shipments of stone from the quarries on the Isle of Wight and in Normandy that were needed for the building of Lewes Castle and Priory. Other trading commodities followed and certainly by 1150 Seaford had become a busy market centre. The market place was initially on the waterfront, and therefore probably somewhere along Steyne Road. The likeliest place is at the junction of South Street and Steyne Road: the triangular open space now occupied by the Jubilee Fountain garden (A on the map below).

The market was moved during the twelfth century, perhaps because market activity got in the way of the loading and unloading of ships, or because market trading was rapidly expanding, as documents suggest, and the market needed more space. It was moved back from the waterfront. There is a documentary reference dated 1180 to Seaford’s market being ‘set back from the shore where it was accustomed to be’.5 So at some fairly early stage, and before 1180, the market was moved inland from its waterfront location to The Crouch (B).6 ‘Set back’ is a good description of Crouch Square’s location relative to Steyne Road.

The 1839 Tithe Map, with the likely locations of the Norman market (A) and later medieval market (B). The green area along the bottom of the map is where the Ouse estuary, and Seaford’s harbour, lay in the middle ages.

Crouch Square would at that time have been on open land, situated on a low hill to the east of the town. It may be that its presence to the east stimulated the town’s growth in that direction between 1200 and 1348. By 1348, the built-up area had extended as far as the west and north sides of Crouch Square. Maps of the Sutton Estate dating from the 17th and 18th centuries show open farmland coming right up to East Street’s eastern road wall (Home Furlong) on the east side of the square and right up to Crouch Lane’s eastern road wall (Crouch Field) on the south side. The market ceased to be held after 1712, but it could not have been held on land that was marked on estate maps as farmland in both 1624 and 1740. This means that the market was not held in what are now Crouch Gardens, as is sometimes said; the gardens occupy what was formerly the western end of Home Furlong; it was farmland. Conversely, all three estate maps clearly indicate that Crouch Square was considered part of the town, and therefore a potential market site.

Crooked Lane is given the name Hangmans Way on the 1624 estate map. There was a widespread medieval European tradition of publicly executing criminals in the town square, so this alternative name for a lane leading into the square may help to corroborate the identity of Crouch Square as Seaford’s market square.

Seaford’s thirteenth century trade included imports of coal for lime-burning and wine, and large exports of high quality Downland wool. Seaford had 16 resident wool merchants and in 1293 exported 20 shiploads of wool, more than any other Sussex port.7

Later, Lewes took over the market roles not only of Seaford but of other small towns in the area, partly because it was a better road route centre. But even after the decline of Seaford’s market, Crouch Square retained its identity as an open space. On the draft Ordnance Survey map of 1805, Crouch Square is conspicuous as a roughly square open space, defined by buildings to west, north and east, open to the south, but its boundary was marked in that direction by what seems to be the present flint wall. The published OS map of 1813 shows a very similar arrangement, but with buildings continuing from the east side of the square up East Street. The Tithe Map of the 1830s shows the same arrangement even more precisely: a roughly square space that was consciously demarcated and respected, and not built on. It may also be that the phasing out of the market during the late seventeenth century led to a quietening of the area, making it an attractive location for upmarket residences: during the period 1720-1850 Crouch Square was developed on all four sides with large high-status houses: Seaford House and Stone’s House to the west, St Faith’s to the north, Crouch House to the east and Crouchfield House to the south. In the 1851 census there were only about 30 domestic servants altogether in Seaford, but a fifth of them lived in houses clustered round Crouch Square. The square was a significant focus.

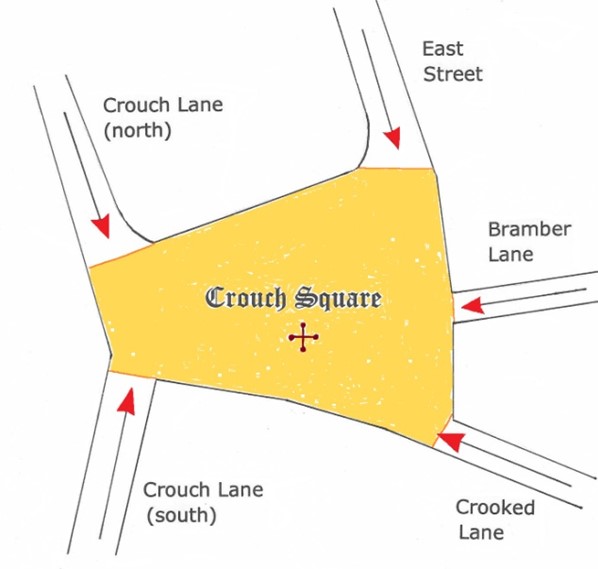

The system of narrow lanes converging on Crouch Square has a distinctly unplanned typically medieval character (still) and again indicates that it was a focus of activity in the middle ages. The roads leading into Crouch Square are Crouch Lane (north), Crouch Lane (south), East Street, Bramber Lane and Crooked Lane.

Crouch Square on the 1830s tithe map; a conspicuous reserved open space.

The road at the bottom is Steyne Road.

The sarsen stone

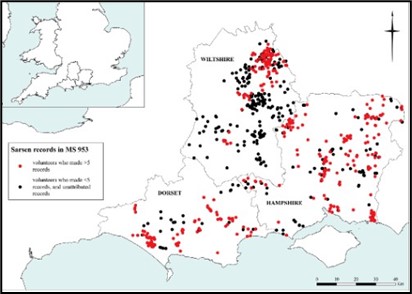

The sarsen stone near the centre of Crouch Square (the cross on the first map) is typical of the sarsens that naturally lie scattered randomly across the chalk downlands of southern England. They originated as a discontinuous layer of silcrete, a very hard sandstone formed by the cementation of Tertiary sand beds in a pan or lake setting. This layer rested on top of the chalk. It was eroded and fragmented by weathering long ago, probably before the onset of the last Ice Age, and the remnants have been gradually lowered as the chalk Downland has weathered down. Some sarsens have been moved from their original locations and gathered, five thousand years ago, to create megalithic monuments such as Avebury and Stonehenge, though there is no certain evidence that this happened in Sussex.8

872 sarsens have been identified and mapped in Wessex. (Sarsen stones in Wessex project) Sussex has far fewer sarsens, though unfortunately they have not been mapped like the ones in Wessex.

In Sussex sarsens have more often been moved to field edges or into villages (as at Falmer) to make the fields easier to manage. Some have been moved to protect important buildings. The two outer corners of Alciston tithe barn are still protected from accidental damage from carts and wagons by large sarsen boulders put in place in the middle ages.

The sarsen stone in Crouch Square measures 122cm north to south and 117cm east to west. The upper surface is flat and smooth. Sarsens are naturally irregular in shape, often knobbly, so this smooth one-metre-by-one-metre surface would appear to have been deliberately dressed. The stone is tilted, with its upper surface sloping gently down to the south. The upper edge sticks up out of the ground and part of the stone’s underside is visible. From this we can see that the slab appears to be about 25cm thick. The edges are abraded and smooth, except at the northern ‘corner’, which appears to have been broken in relatively modern times.

Plan and section of the sarsen stone

What the sarsen slab is doing in the middle of Crouch Square is an important issue. Clearly it is ‘in the way’, so it must have had a function of some kind. It is possible, precisely because it is close to the centre of the square, that it represents part of the medieval market cross. The design of Seaford’s market cross is not known, but it is likely to have been modest in scale, and similar to those of other small market towns, like nearby Alfriston.

Market crosses usually consist of a stone pillar topped by a small stone cross. This was mounted on a plinth or rostrum, often in two or three tiers. The sarsen in Crouch Square could easily have been part of the cross base. Other, smaller stones mortared to it could have been removed for recycling. The largest stone may have been left in place because it was too heavy to move easily. The sarsen may originally have been set horizontally, but tilted as a result of road-making nearby.

A sacred stone?

There is an alternative or additional possibility. In the thirteenth century there was a rock situated on the waterfront at Seaford, probably somewhere along Steyne Road, perhaps beside the market place. It was held in special regard and even had a name. It was known by the extraordinary name Whasbetel. Contemporary documents explain that it was used to mark the boundary between the right of wreck of Peter of Savoy, lord of Pevensey Castle, and that of Earl Warenne, lord of Lewes Castle. Anything washed ashore to the east of Whasbetel might be claimed by Peter of Savoy, anything to the west might be claimed by Earl Warenne. Boundary challenges relating to Whasbetel were accompanied by strange rituals.9

The rock’s use as a boundary marker gave it civic significance, as did its having a proper name. But the name contains something else. ‘Betel’ or ‘betyl’ is not an English word at all, but a Hebrew word meaning a sacred boulder, a boulder inhabited by a deity. The rock called Whasbetel was still on the waterfront in 1262, by which time the market had been moved and was well established up at the Crouch, but it is possible that if the rock’s original use faded and it was found to be obstructing port activity yet still had some ceremonial value it might in the later middle ages have been taken up to the new market place. The stone was nevertheless still on the waterfront during the widowhood of Queen Eleanor (Edward I’s mother), 1272-1291, when she had right of wreck east of Whasbetel.10

*************

N.B. I have moved Rodney’s Sources and Notes to the very end of the blog, well I do like to have my say!

******************

Thank you Rodney, for such a fascinating article on the medieval history of the market cross.

The question is how can we ensure this area is enhanced and celebrated? After all it is an important part of the history of our town. How many other towns in East Sussex can lay claim to having had a medieval market cross and still have a sarsen stone, possibly a sacred stone inhabited by a deity?

Do we have any local tradespeople that could possibly design and make a wooden sign that could be placed on one of the patches of green? If we do will Seaford Town Council allow it to be placed as a feature? We could put some memorial benches in the area and make it a place where weary travellers can rest.

Come on Seaford let’s find a way to spruce up the area and make the market square and sarsen stone a heritage asset the town can be proud of. Maybe we could have a treasure trail where tourists search for Seaford’s secret treasures. I’m sure we have many more that could be added to a treasure trail.

Rodney has written many books on local history. I’ve listed below his books that relate to the history of Seaford.

On Blatchington Hill: History of a Downland Village

On Blatchington Beach: a Village and the Sea

Forlorn and Widowed: Seaford in the Napoleonic Wars

The Seaford Axe Hoard

Ancient Seaford: Ice Age to Napoleonic Wars

History of Seaford: Worlds of Wonders

There are also some church guides: Berwick, Selmeston, Alciston, Arlington and Wilmington

If you are interested in buying any of them, please contact Rodney either by email (rodneycastleden35@gmail.com) or by post (Rodney Castleden, Rookery Cottage, Blatchington Hill, BN25 2AJ). He will deliver copies to you anywhere in Seaford.

Sources

OS maps from 1805 and 1813.

Tithe Map 1839

Notes

1 Harris, R. 2005 Seaford Historic Character Assessment Report. LDC: Sussex Extensive Urban Survey.

2 Lynn Lawson, personal communication. Lynn is researching a book about William Tyler Smith.

3 Shorter Oxford Dictionary.

4 Lower, M. A. 1854 Memorials of the town, parish and Cinque Port of Seaford, Sussex Archaeological Collections 7, 73-150.

5 Pipe Roll, 26 Henry II.

6 Gordon, K. 2010 Seaford through time. Amberley.

7 Pelham, R. A. 1934 The distribution of sheep in Sussex in the early fourteenth century. Sussex Archaeological Collections75, 128-35.

8 Summerfield, M. A. and Goudie, A. D. 1980 The sarsens of southern England, in Jones, D. (ed) The shaping of southern England. IBG Special Publications 11, 71-100. Whitaker, K. A. 2020 Sarsen stones in Wessex project. Google Scholar.

9 Moore, S. A. 1888 A history of the foreshore and the law relating thereto. London: Stevens and Hayes.

10 Salzman, L. F. 1943 The hundred roll of Sussex. Part 2 Rape of Pevensey. Sussex Archaeological Collections 83, 35-54.